Bill Bradbury: An Oregon Story (Part 2)

William Chapman Bradbury III – known to everyone he met as Bill – was a beloved figure in the world of Oregon politics and public affairs from 1981 through 2018, serving as a state legislator and Secretary of State. Born on May 29, 1949, in Chicago, Illinois, Bill died unexpectedly in April 2023 while on an around-the-world cruise with his wife, Katy Eymann. His passing set off a flood of fond remembrances from people throughout the state and beyond who had known him or were touched by him. – Robert Bailey

Open Spaces is pleased to present three articles about Bill. The first, by Robert Bailey (Part 1), a longtime friend and colleague, is a recounting of Bill’s personal background, his entry into Oregon and his emergence as a public figure. This article is based on remarks by Robert Bailey at Bradbury’s public celebration of life in October, 2023. The second article, presented here, shares remarks made at Bill’s celebration by Dr. John Kitzhaber, and the third is a personal tribute from Bill’s youngest daughter, Zoe Bradbury (Part 3). Together, these three pieces provide a strong sense of the man, his life and the legacy he left.

_________________________________________

My Friend and Fellow Traveler Bill, the Big Chinook

by Dr. John Kitzhaber

I am grateful to have this opportunity to say a few words about my friend Bill, who I called the Big Chinook, and what he meant to me—actually, what he means to me.

I first met Bill in 1979, in the restaurant at what was then the Windmill Inn in Roseburg. I was serving my first term in the Oregon House and I think Bill was as shocked as I was that I defeated an incumbent Republican in Southern Oregon the year before. He said something to the effect of “well, I figured if you can get elected down here anybody can,” a statement accompanied, of course, by his infectious grin. I told Bill I was confident he could get elected, and encouraged him to run. He was elected to the House the next year, the same year I ran for the Senate. And that was the beginning of a friendship that lasted over forty years.

Bill was my best friend in the legislature and the Majority Leader when I was Senate President. He was the architect of Oregon’s watershed councils, and we worked together to put in place Oregon’s first public instream water right, the state hydroelectric policy, and to develop and implement the Oregon Plan for Salmon and Watersheds. He was a gifted and passionate public servant, a huge heart, and a beautiful human being. And I miss him very much.

We are gathered here today to celebrate his life—which is as it should be, because no one celebrated life more fully than Bill. At the same time, I am sure we all feel a sense of loss – I know I do. Speaking for myself, part of that is selfish, in the sense that I can’t reach out and touch him, or hear his voice in the same way I could. But in another sense, I feel as though he never really left. We just need to look for him—which is what I want to talk about today.

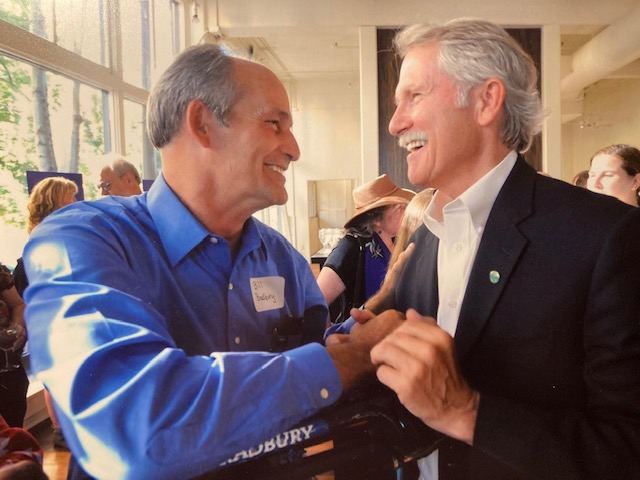

This picture of us embracing at the Capitol captures our public lives and the joy and satisfaction we shared in service to Oregon. I love this picture. But the one that captures the deeper level of our friendship is this one taken on the Rogue River in the 1980s. Bill was cooking steaks and he always insisted on patting Pickapeppa Sauce onto the meat with his hands. For some reason, I have the Pickapeppa bottle cap in my eye. I have no clue why, except I suspect there may have been some Wild Turkey involved.

In this picture, we are camped river left about half a mile below Whiskey Creek at a place called Cave Rock. Some of you may know it. Last month my son and I floated the Lower Rogue River Canyon, his first trip rowing the whole section from Grave Creek to Foster Bar on his own—a rite of passage in the Kitzhaber Family. We camped at this very spot, and because I knew I was going to speak at this celebration of life, and was looking for inspiration, I dedicated the evening to telling Logan about my friend, the Big Chinook. And here is what I told him.

I told him that Bill and I both loved rivers and we loved wild salmon. We loved salmon because the life of a salmon is dedicated to the future—to nurturing, sustaining and giving to that which will follow. Salmon spend much of their lives swimming upstream, but with a clear and unshakable purpose—some make it to the gravel beds, where they were born and plant the seeds of tomorrow, others die in the attempt, and yet, in death, give their bodies to the river, providing the nutrients necessary for the survival of the next generation.

Bill too swam upstream, through adversity that many of us will never know, always with joy and great good humor, and with a clear and unshakable purpose of his own: to make Oregon a better place, to plant the seeds of tomorrow. I think we can all agree that his journey was a spectacular success.

I told my son that Bill and I loved rivers because, like each and every one of us, they are at the heart of an endless cycle as old as the universe and as young as the mist chased up the canyon walls by the morning sun. Bill and I—and some of you here today—rafted the great rivers of the Pacific NW —the Umpqua, the Rogue, the McKenzie, the Santiam, the Deschutes, the Snake in Hells Canyon, and the Middle Fork of the Salmon.

I spent many nights with Bill, camped on sandbars, deep in some canyon with a canopy of brilliant stars overhead, and the sound of crickets and frogs and the murmur of distant rapids filling the air. In those magic places we were able to feel what only a river can teach, something that words are incapable of expressing – the spirit and essence of who we are, of our relationship to our natural environment and to one another. Something intangible yet palpable, ancient yet young and new, the sense of awe that comes with the connection to all that was, all that is, and all that will be. Bill understood these connections more than anyone I have ever known. And, in his own way, he shared them with us.

I want to read a passage from Stronghold, a book by Tucker Malarkey, about wild salmon. Here she is describing spawning Sockeye salmon in the braided steams at the very headwaters of Bristol Bay.

Floating in slow, calm, rain-stippled channels, salmon were everywhere, both spawning and dying. The boundary between life and death here was blurred to the point of disappearing. I realized that this was where the biomass that fed, the ocean, began, where nutrients from decaying salmon flowed out from rivers and streams and were carried north by ocean currents. These frigid waters held the oceans richest soup, where whales, seals, and Orcas fed. Salmon fed here too and, with their next migration, returned the nutrients to the land to start the cycle anew.

This is the sentence I want you to hold onto: “The boundary between life and death here was blurred to the point of disappearing.” That boundary is a human distinction, an artificial construct, not necessarily a real one. I think Bill understood that.

When I think of Bill, I don’t think of Salem or politics or public policy. I think of a flashing silver body in the roar of Rainie Falls, the raw power of Blossom Bar, an osprey cutting the water like a knife and rising in the soft evening air with a shivering trout in its talons. I think of an otter tracing a “V” across the glassy surface at dusk, an eddy, wood smoke at dawn, a bear in camp, the scream of an eagle echoing down the walls of the canyon. Bill is all of those things. We just need to look for him.

On our second day on the Rogue last month, my son and I were floating on a green ribbon of cold, clear water in the deep current below Horseshoe Bend, when a fish rolled just in front of the raft. Without thinking, I said: “Bill, there you are… there you are.” Logan looked confused for a moment, and then a smile of comprehension slowly spread across his face. “Ah” he said – “It’s the Big Chinook.”

Exactly. And so, it is.

Comments, thoughts or questions? Email us now!