Bill Bradbury: An Oregon Story (Part 1)

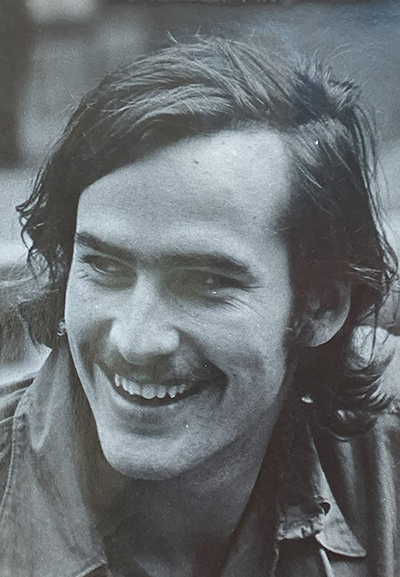

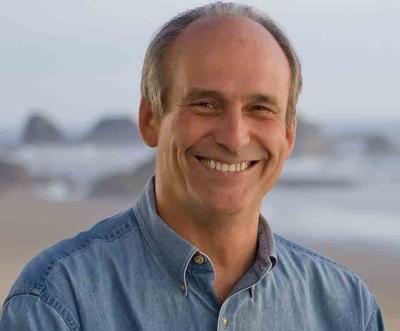

William Chapman Bradbury III – known to everyone he met as Bill – was a beloved figure in the world of Oregon politics and public affairs from 1981 through 2018, serving as a state legislator and Secretary of State. Born on May 29, 1949, in Chicago, Illinois, Bill died unexpectedly in April 2023 while on an around-the-world cruise with his wife, Katy Eymann. His passing set off a flood of fond remembrances from people throughout the state and beyond who had known him or were touched by him. – Robert Bailey

Open Spaces is pleased to present three articles about Bill. The first, by Robert Bailey (Part 1), a longtime friend and colleague, is a recounting of Bill’s personal background, his entry into Oregon and his emergence as a public figure. This article, presented here, is based on remarks by Robert Bailey at Bradbury’s public celebration of life in October, 2023. The second article shares remarks made at Bill’s celebration by Dr. John Kitzhaber (Part 2), and the third is a personal tribute from Bill’s youngest daughter, Zoe Bradbury (Part 3). Together, these three pieces provide a strong sense of the man, his life and the legacy he left.

_________________________________________

Coming into Oregon: The Life of Bill Bradbury

by Robert Bailey

It is often only in retrospect that it is possible to see how a person’s life journey unfolds in delightful, often unpredictable ways even as there is a consistency in the journey that seems almost pre-ordained. Bill Bradbury and I were friends for more than 50 years, influencing and intersecting with each other’s lives in many ways. It has been a singular experience to dive into my memories of Bill over the past 50 years, some I recall in vivid detail as if they were yesterday while others are only a vague recollection waiting for details from family and friends. I am indebted to his family, especially, for providing new information and insights and correcting my recollections. They honor me with their trust in sharing Bill’s story.

As with all stories of a friendship begun in the springtime of life, it is tempting to tell tales. I might begin with the story of a small Cessna airplane piloted by Bill Bradbury – with me as the lone passenger – as it flew into a wall of dense fog low over the Umpqua River near Reedsport. If we were sitting around a driftwood campfire on the beach, the tale would turn dramatic and I would lean in and say “no kidding: there we were – and it was not good.”

Perhaps, I would recall a blistering hot August day in 1972 when we drove to the Oregon Country Fair site near Veneta and sat in the thin shade listening to the Grateful Dead in a now-legendary concert that benefited the Kesey family’s Springfield Creamery.

Or, I might relate the time in 2008 when we were in the Chicago airport and Bill stepped aside to take a call from Hillary Clinton who was seeking his support for her bid to be the Democratic nominee for president.

But instead, I want to zero in on the fact that a young man – a kid really – from Chicago by way of Swarthmore, Pennsylvania, and San Francisco could arrive in Coos County and within a few years step into public life and leadership from the conservative, rural southern Oregon coast. Who was this remarkable young man? What happened to shape him before he arrived? How did he find his footing in a new home that led in only a few years to a public life?

___________________________________________

Coos County is far removed both geographically and culturally from the big city neighborhoods near the University of Chicago, where Bill’s father was a Professor of Sociology, or the suburban tracts of McLean, Virginia, near Washington, D.C., where the family lived for several years before returning to Chicago. His parents, William and Lorraine, both socially conscious Friends (Quakers), infused Bill and his two older sisters, Joan and Katharine, with the ethics and democratic traditions of Quakers, especially the idea that each person is worthy of respect and an equal chance. Looking back, it is clear these values informed his outlook on life and shaped his interactions with others even though he rarely spoke of them directly.

Interestingly – and significantly – from a young age, Bill developed a precocious interest in cooking and food preparation, helping his mother plan and cook for the frequent community dinners shared with friends in the university neighborhood. His family and friends attest that hardly a meal went by that he did not exclaim over the food, relish every bite, and proclaim this to have been the best meal he had ever eaten! One day, his love of food and cooking would lead him to Oregon.

Bill’s life changed abruptly and tragically in the summer of 1958 when he was nine years old. Bill, sister Kathy, and his parents were driving home to Chicago from a summer in Seattle where his father was studying Chinese language. In rural Montana, their car was involved in a horrific crash. Both parents died. Bill was seriously injured. Amazingly, Kathy was unhurt.

In the aftermath, Bill and his sisters were welcomed into the home of Bill’s maternal aunt, Kay, uncle Paul, and cousins Andy and Steve Gay in Swarthmore, Pennsylvania. The Gay family also ascribed to Quaker beliefs, which gave Bill and his sisters a sense of continuity during a dark time. Summers found him in Quaker-sponsored camps in New Jersey and Vermont. In August 1963, five years to the day after that car crash, Bill was with his sister Joan on the Capitol Mall in Washington, DC, and heard Dr. Martin Luther King give his now-famous “I Have a Dream” speech.

At 16, Bill returned to Chicago to live with his oldest sister, Joan, by then his guardian. Now over six feet tall, he enrolled for his final two years of high school in University of Chicago Lab School which he had previously attended as a very young and fondly remembered elementary student. Here, through a student newspaper he helped to found, he began to delve into journalism and photography, taking portraits of the people and community in his life.

In the fall of 1967 Bill set out for Yellow Springs, Ohio, to attend Antioch College, a small, somewhat unconventional college where students alternated between classroom studies on campus and learning through work in the “real” world. His major interest in communications and media led to an internship with KQED-TV, a public television station in San Francisco in the summer of 1968.

His arrival coincided with a city-wide strike by union workers for San Francisco newspapers which meant that there were no newspapers! To fill the news vacuum, KQED-TV had created “Newspaper of the Air,” for which reporters wrote news stories as for a print newspaper and then, sitting in a group in front of a TV camera, each read their story live. Although an intern, Bill was immediately included as an on-air reporter at the ripe age of 19. It proved such a good fit for both Bill and the station that in fall of 1969, rather than return to the Antioch campus, he extended his work for another year.

As is well documented, San Francisco was a cauldron of cultural, social, and artistic ferment and exploration during this time and Bill was immersed in that cauldron. He became involved with a group of friends, including Lynn Adler and Jules Backus, in forming a photography collective dubbed Optic Nerve, one of many innovative organizations comprising Project One, a loose “technological commune” of intellectuals, artists, activists, social organizations, and others housed in a huge warehouse and former candy factory in the middle of the city. They built and outfitted a large darkroom in the warehouse. But a new medium, portable video, soon took center stage. Meanwhile, other Antioch College students, including Jim Mayer and Steve Christiansen, who would later join Bill in Oregon, arrived with their own interests in arts, poetry, media and portable video technology.

This technology was, in many ways, simple. A hand-held video camera was attached to a recording machine by a long cord. Black and white images from the camera were recorded onto a small reel of half-inch wide videotape that accepted about 20 minutes of imagery. Audio was fed from a microphone attached to the recorder by a separate cord and recorded simultaneously as a separate track on the videotape. The recording machine fit in a satchel worn over the shoulder or stuffed into a backpack. The process of editing Images and sound from the little reels of videotape into a program on a master videotape was initially quite primitive, more-or-less hand-operated, and time consuming. It is hard to appreciate today, with the ease of high-resolution color video instantly available on phones and doorbell cameras, but this technology was revolutionary. It liberated television from the confines of the studio and put it into the world of real people.

Somehow, while in San Francisco, Bill found time to earn his private airplane pilot license. He also volunteered with the local chapter of the American Friends Service Committee counseling young men on their options for the military draft. His demonstrated commitment to his Quaker beliefs enabled him to receive Conscientious Objector status from his local military draft board in Chicago, which had a record of denying that status for most applicants. In summer 1971, he landed a job at a small restaurant where he could indulge his love of cooking. It was about this time that he and his girlfriend got a tip that a restaurant was for sale on the Oregon coast in a small town named Bandon.

_________________________________________

Bandon sits on the south side of the Coquille River where it flows into the Pacific Ocean some twenty miles south of Coos Bay. This stretch of the Oregon coast was – and still is – somewhat isolated from the rest of the state, cut off from the Umpqua and Willamette valleys by the Coast Range Mountains on the north and east and the rugged, remote Siskiyou Mountains to the south. To the west lies the Pacific Ocean, which, for more than a century, provided the main access to the outside world. Timber production, agriculture and fishing were – and still are – major economic drivers as they had been since the mid- to late-1800s. But after World War II, Bandon increasingly became Bandon-by-the-Sea, cultivating an image as a coastal resort town and retirement destination.

There is a certain timelessness to the region, especially the hinterlands away from the coast itself. Even today, when I drive the rural roads from Bandon or Coos Bay into the valleys and mountains of Coos County, the primary clue that it is not 1972 or even 1942 is the model of the pickup trucks passing by.

I grew up in Coos County, as did my parents, so I had grandparents, aunts, uncles, cousins, and other family members nearby that I never could keep straight. But between visiting these relatives, camping with my Boy Scout troop, going on family blackberry-picking expeditions on graveled logging roads, and accompanying my dad to far corners of the county on floor-covering jobs, suffice it to say that I knew Coos County and a good portion of neighboring Curry and Douglas counties.

In summer 1971, my sharp-eyed mother spotted a Help Wanted ad in the local newspaper for a cartographer in the new Coos County planning department. I had taken a class in mapping in college and needed a job so I applied. Fatefully, I got the job, much to my mother’s relief! But in a few months, I found myself the Acting Planning Director with a primary task of assisting the county commissioners to enact a zoning ordinance, a move so politically fraught that only a year or so before the voters had recalled the entire board of commissioners for attempting to do just that. But a 1969 state law, Senate Bill 10, required counties to enact such zoning or the governor – in this case Tom McCall – would do it for them. The commissioners were determined that they should be the ones to do it. So, even with longish hair and sideburns, I was a county bureaucrat and stood out in a community of seekers, cultural refugees, drop-outs, artists, craftspeople, musicians, Vietnam veterans battling their traumas in remote cabins, and others on their Karmic Road.

I had rented a vacant log house on rural property on Bear Creek, just east of Bandon out of the coastal fog belt. I struck up a friendship with Bill Marino, a young man recently out of the Marine Corps who ran a leather shop in Bandon. I soon invited him to park his pickup camper on the property I was renting because…why not? One spring day in 1972, I returned home from work at the county offices in Coquille to find Marino having a beer with a young couple new to the area who he had met at their restaurant in Bandon. He introduced Bill Bradbury and his girlfriend Betsy Harrison. From the get-go, we all hit it off and our friendships began.

Bill was all of 23 years old. I was 27.

Of course, I was taken with him! Who was not – with his engaging personality, wide range of interests, his huge sense of humor and an amazing laugh? He was the brightest light in any room he entered. That Thanksgiving he further endeared himself to me by bringing creamed onions for the dinner, which he said was a traditional family dish. I had never even heard of creamed onions! At this point I knew nothing of his background, his family, or his path to Bandon. That background would slowly unfold, even to today.

We bonded over the usual: music, food, culture, and politics of the time. As the months rolled by, other former Antioch students arrived in Bandon, creating a very creative community. But I was most surprised that he was genuinely – almost unnervingly – interested in my work with the county, the idea of zoning and land use, and what it meant for local communities. As our friendship developed over the coming months, this became a central theme of continual interest to him.

He and Betsy had come from San Francisco to Bandon almost as a lark. Along with two other friends, they bought the Two Seasons restaurant, a weathered two-story affair on 11th Street near the ocean bluff. It seemed like a good idea: the nearby beach attracted a steady stream of tourists who drove right by the restaurant in summer. Bill loved to cook and the thought of operating a restaurant was appealing, especially one that would be busy for the summer tourist season but during the slow winter months would leave time for other more creative pursuits. And, he and Betsy could live in the apartment above the restaurant!

But they soon found that cooking for tourists in a restaurant meant deep-fat fryers for fish and French fries, salad dressing by the gallon, and multiple hamburgers at a time sizzling on a hot grill. It was not cuisine and, at times, not fun. But it was a start.

For me, it was great to have a friend with whom I could talk about my work, the political and technical aspects of my job because, frankly, I had no idea what I was doing and neither did the county commissioners. Bill’s collaborative style, honed (I later came to understand) by his time with Optic Nerve and Project One, made him an ideal sounding board to help me feel my way. Looking back, his interest in land use and community in Bandon and Coos County was a lens – a frame of reference – through which he learned about, came to appreciate, and became involved in his new home.

Bill brought another lens through which to view and connect with the county and, eventually, for the county to view and connect with him. This lens was on his portable video camera, the brand-new technology that he and friends at Optic Nerve had begun experimenting with in San Francisco. These two lenses soon converged and proved instrumental in connecting him to Coos County and to Oregon. It was one thing to play with this technology in the context of artists and activists in San Francisco and quite another to employ it in Coos County.

About the time Bill and I met, the county had been asked to approve a development of several hundred homes on the hillsides above South Slough, an arm of Coos Bay near Charleston. Residents of the area, who had been meeting over the lack of sewers, were unnerved by the thought of such development but were positively horrified by the proposal for sewage lagoons in the saltmarsh along the slough. The county had no zoning, no land use planning and only rudimentary subdivision regulations. The Oregon Department of Environmental Quality and the federal Environmental Protection Agency were brand new so there were no water quality regulations for such proposals. The only effective land use regulatory hammer available was the county health department sewage disposal code. Opposition to the development was fierce and Bill wanted to understand the uproar. Video reporting was a way to learn.

So, on a July day in 1972, a few months after we met, Bill and I drove north to the dock in Charleston at the mouth of South Slough to meet Jerry Rudy, a county planning commissioner who was also director of the University of Oregon Institute of Marine Biology in Charleston. We piled Bill’s video gear and ourselves into a small, open boat with Jerry at the throttle and headed into the upper reaches of the slough. The broad estuary soon narrowed and we glided over fronds of eelgrass waving in the water, the muddy bottom only a few feet below. The channel narrowed and became flanked by golden marsh grass extending to the foot of the steep hillsides covered in trees and brush. As we went, Jerry explained what we were seeing, pointing out why the estuary was so valuable and what was at risk from development. Bill video-recorded it all at water level in what turned out to be beautiful black and white imagery. The next day he rented an airplane in North Bend and we flew over Coos Bay and South Slough as I pointed the video camera at the panorama below or, several times, as I held the rudder steady while he took the camera.

Back in Bandon, we talked about what message the video should deliver, the images he would use, and the script I would read. Then, upstairs above the restaurant, he went to work with his little editing deck and a 10-inch black and white monitor to craft a short video about South Slough – less than 10 minutes – which he ended with Joni Mitchell singing the already famous lines from her song Big Yellow Taxi “Don’t it always seem to go/That you don’t know what you’ve got ‘til it’s gone?” I thought the song was a little too editorial but Bill loved it and so we left it in. Over time, these words would come back to us as prescient.

A month or so later, in early September, Bill and I drove north to Florence to show the video to a meeting of the Oregon Coastal Conservation and Development Commission. The OCC&DC, as it was known, had been created by the 1971 legislature and charged with the audacious task of writing a plan for protecting the Oregon coast. Concerns over Oregon’s estuaries, as voiced especially by Governor Tom McCall, had been one of the reasons the legislature created this commission. From my work with Coos County, I had come to know the Executive Director of the OCC&DC, Jim Ross, who had grown up on Ross Inlet, an arm of Coos Bay. He was willing to schedule time for the commission members to watch the video.

The meeting was held in the Pier Point Inn, a hotel overlooking the Siuslaw River estuary. Bill borrowed a large TV set from the hotel and connected his editing deck to it. Bob Younker, an OCC&DC member representing the Port of Coos Bay, was of tribal descent; his family had lived for generations alongside South Slough. He introduced Bill, who then played the video. Afterwards, a somewhat bemused commission discussed what they had seen and what they should do in response. In the end, the commissioners voted unanimously to urge Coos County to reject the development. The county did so some weeks later.

Beyond this immediate outcome, the video shined a spotlight on South Slough and made this remote area known to people who had never been there. We could not know that, within a few years – and after much effort by many people and a bit of luck – a big part of the upper end of South Slough would be designated as the Nation’s first National Estuary Sanctuary under the then new national Coastal Zone Management Act enacted a month or so before the OCCDC meeting. And we would never have dreamed that, 25 years later, Bill would be Secretary of State and a member of the State Land Board, which owns and manages South Slough as a National Estuarine Research Reserve.

At the time, we were pleased and somewhat amazed by the reception to the video and the effect it seemed to have. He was eager to find another project. We soon decided that he should create a video to explain and illustrate the new zoning ordinance that I was working on. The county commissioners had seen Bill’s South Slough videotape, liked what they saw, and were happy to get any help with the politically touchy zoning ordinance.

Amazingly, a postcard arrived in the mail from Southwestern Oregon Community College seeking proposals for projects using new telecommunication technologies to promote public understanding and participation in natural resource issues and land use affecting their community. It was a perfect fit – proverbial manna from Heaven!

Bill jumped into action, wrote a short proposal, and soon landed a small grant to produce the zoning video. Months before, the county commissioners had been adamant that the public be involved in creating and applying the zoning ordinance. In response, I had organized community groups throughout Coos County to engage land owners. Bill attended several of these far-flung events in Powers, Bridge, Allegany, and other communities where he met people and videotaped the discussion, capturing such scenes as property owners gesturing and pointing to the county assessor maps as they swapped stories.

Over the next few weeks, he drove the backroads of the county, videotaping scenes of various land uses and interviewing landowners and residents he had met at the community meetings. We crafted a script that explained each zone. Then he sat down and created a program – in black and white – about 30 minutes long that, in many ways, de-mystified the zoning ordinance and cast it in terms people could understand.

That fall, 1973, the local TV station, KCBY-TV, broadcast the video as public service programming, which meant that it was shown on a Sunday morning and late on a weekday evening. It was a hit with the public and the county commissioners. The zoning ordinance was eventually adopted with little political repercussion. In a little over a year since arriving in Coos County, Bill was helping to shape its future – and his own.

This zoning video attracted additional funding from the Oregon State University Extension Service for a longer, more in-depth video about the future of land use in Coos County. Nationally, the Extension Service was advocating for land use planning to protect agricultural lands from urban sprawl. Oregon, which seemed to be making steps toward such planning, could provide a pilot project to show the rest of the country.

To make this video, Bill returned to many of the people he had met. By this time a friend from Antioch College by way of San Francisco, Steve Christiansen, had arrived to work on this project under the heading of “Coos Country TV.” Together they toured the county, interviewing and recording people as they worked. The result was beautiful black and white video images of Bob Geaney, a sheep rancher, interrupting his commentary to whistle commands to his dog darting across a far hillside as it worried a flock of sheep into a new field; a dairyman (and future county commissioner named Gordon Ross) hooking a milking machine to a very large cow as he talked about the value of local foods; two Waterman brothers near Myrtle Point felling a tall second growth Douglas fir in dawn’s gray light near a spot where, forty years earlier, they had helped their father do the same; a fisherman swaying on the deck of his boat in Charleston; and women skillfully slicing fish into filets as they talked. Bill was clearly taken with the authenticity of these people and the lives they led. Through repeated visits, they came to know and to trust him.

Bill rented a house on the cliff above the beach just south of Bandon where he and Steve set up a small video production studio. I had left the county planning department by this time and began working with Bill, Steve and two other friends, Pia Perniciaro and Joan Schoonmaker, on this project. We met for hours each day, editing the new video with the working title of “Common Sense” and planning how to bring it into public view.

The house, dubbed “The Edge,” was spacious. It featured a well-appointed kitchen where Bill, when not working on video projects, cooked, and held forth with friends, new and old alike. He was passionate about his coffee and insisted on using an hourglass-shaped Chemex carafe, pouring boiling water through freshly ground coffee spooned into a paper filter. The days were measured in the number of carafes of coffee consumed.

In between the editing sessions on “Common Sense,” we walked the beach below the house, hunkered against the wind, picking up colorful rocks from the glistening sands at low tide and odd pieces of driftwood at the high tide line. I had grown up doing this, but for Bill it was all new and he relished it. He often drove his sturdy red Toyota Land Cruiser pickup, dogs Putney and Brutus in the back, to other nearby beaches to explore what the tides had to offer. The truck got terrible gas mileage but was rugged and could easily clamber over rough trails to remote beaches.

We were surprised in late 1973 to learn that Bill’s work with video and community meetings had come to the attention of Ken Kesey, the famous author (and counter-culture figure) who had landed back on his family’s farm near Springfield, just east of Eugene. Ken, now with school-age children, had become involved in the community around the safety of kids crossing a busy highway to get to school. Eventually, though, he and others in his circle were discussing ways to involve the public in broader, more far-reaching topics that touched on land use, energy, democracy, health care and other issues. They conceived of holding a series of town hall meetings around Oregon to try to spark thought and discussion and decided that these should be televised. Ken had heard via the grapevine that something like that was going on in Coos County and invited us to come talk.

So, on a cold winter day in early 1974, Bill, Steve, Betsy Harrison and I drove icy roads to Eugene to meet with Ken to compare notes and brainstorm ideas. The freeway became progressively more treacherous as we approached Eugene and we barely made it to a radio station where, for some reason, we had agreed to meet. The ice prevented Ken from joining us and we were afraid to leave. So, we spent the night on the floor in the station waiting for roads to thaw a bit. By noon the next day, Ken was able to reach the station, skating down the icy road sporting a wild crocheted hat with ear flaps and oddly pointy top. Carefully, Ken guided us to the comfort of a wood stove fire in his home in a converted barn.

In the end, Ken and friends convened a dozen town hall meetings around Oregon, similar to the dozen town hall meetings we would hold in Coos County. Their effort resulted in representatives from each of the town hall meeting convening in a final, large statewide event dubbed “Bend in the River” in July 1974 at Central Oregon Community College in Bend. Among those in Kesey’s friendship circle at Bend in the River was a young man named Bill Murray who went on to fame as a comedian and actor. At the time, though, he was just a guy holding a microphone.

By late summer, 1974, Bill and Steve completed “Common Sense,” an hour-long story in black and white. A unique and somewhat compelling aspect of the video was that there was no “Voice of God” narration. Rather, Bill and Steve relied on Optic Nerve experience to let the voices of the people speak for themselves. Editing was difficult because the voices on camera were unrehearsed and unprompted. But the result was a powerful and engaging program.

We scheduled a dozen or so meetings in communities throughout the county to show the program, the same communities where I had held county zoning meetings a year or so earlier. In each community, we asked a local resident to serve as host for the meeting. And so, over the next few months, we drove winding two-lane roads, often in foggy or rainy weather, to each of these town hall meetings to show the program and talk with residents.

In the first few meetings we were nervous because as the start time for a meeting approached, the parking lot would be nearly empty. But we soon learned that at about five minutes before the appointed hour, pickups and sedans would suddenly arrive, splashing through mud puddles in the gravel parking lot, and the hall would come alive as people greeted each other! The local host would introduce Bill who explained the project and what we hoped would happen. He then played the video on a large (and heavy) black and white TV brought for this purpose. Audiences were rapt as they watched and listened to themselves and their neighbors tell their stories. One woman, not fully comprehending videotape recording, commented “we don’t get this channel on our TV.” Afterward, Bill stood before the room and, using his reporter skills, elicited comments and discussion. Each of these sessions was videotaped by Steve while I or Joan or Pia held a shotgun microphone to capture comments from across the room.

We later analyzed the recording of each meeting and selected key parts that were then edited into a single program that broadcast on KCBY-TV. Comments gleaned from the town halls formed the basis for a public opinion survey about land use issues published in the local newspaper, the Coos Bay World, to which people were asked to respond after watching the TV broadcast. The results of the survey were tallied and presented to the county commissioners to help them understand community sentiments about land use planning. In all of this, Bill was the face of the project and by the end had become a local personality!

By now, Bill and his now-wife Betsy had divested themselves of the restaurant, trading it for rural property on nearby Floras Creek where they hoped to establish a long-term family home while he pursued his interests in media with, perhaps, some ranching and small-scale timber management on the side. Public office was nowhere to be seen on his list of possibilities. Eventually, however, the two agreed to a divorce but remained good friends as they raised two daughters, Abby and Zoe, on the Floras Creek ranch.

Word of Bill’s video and community engagement in Coos County spread. Among those who heard were state officials in Salem working to breathe life into the requirements of Senate Bill 100, the new statewide land use planning law, passed a year earlier. Bill’s Oregon world was about to expand.

__________________________________

In spring 1975, Bill found himself with Steve and video gear, tucked into the backseat of a car driven by Arnold Cogan, the director of the new Department of Land Conservation and Development. Cogan and several members of the Land Conservation and Development Commission were holding community meetings across the wide-open spaces of eastern Oregon to hear from residents what goals the new land use program should pursue. Bill and Steve videotaped the proceedings which they edited into “People and the Land,” an hour-long black and white video. Bill’s horizon in Oregon expanded as he met people, explored their communities, and reveled in a landscape utterly different from coastal Coos County and yet, because of the people, somehow the same.

It was during this time that the Cessna airplane incident occurred. We had flown in a rented airplane from North Bend to Salem in the early morning to attend a meeting with officials from the new Department of Land Conservation and Development to review the community meetings being held across the state. We met in the Governor’s spacious wood-paneled conference room on the second floor of the state capitol, seated around a beautiful large table. As it turned out, Bill and I returned to that room many times in subsequent years. The meeting was run by L.B. Day, a no-nonsense former Teamster Union official who had been appointed by Governor McCall to chair the statewide land use commission. L.B., as he was known, was an irascible character and somewhat skeptical of these youngsters from Coos County with a video camera. We could not have known that ten years in the future, Bill and L.B. would serve together, although from different parties, in the 1985 Oregon Senate.

Our near-miss in the fogbank in Reedsport occurred after the meeting in the late afternoon as we were flyng home. We knew that fog often forms in the afternoon along the coast in summer but blithely hoped today would be different and we would get back to North Bend with no problem. But it wasn’t different. And in that instant of reality, suddenly surrounded by thick fog with no sense of up or down, Bill calmly looked at his instruments, pointed the nose up and into a high right-hand turn to head back upriver away from the fog. As we banked, I glimpsed the forested mountainside dropping away and sighed with relief. Moments later we were in sunshine under a blue cloudless sky. We buzzed over the Coast Range to Eugene where we took a taxi to a hotel, drank a few beers to celebrate our escape, and stayed the night. The next morning, we got back in the airplane and flew without incident to North Bend before the fog formed. We were lucky.

Fast-forward to early 2024: clips from “People and the Land” appear in a documentary video program, “An Oregon Story,” about the Oregon land use program produced by Joe Wilson and Bill’s good friend, Jim Gilbert, in 2023 for 1000 Friends of Oregon, a long-time land use watchdog organization founded by Governor McCall. These video segments, captured by Bill and Steve in black and white, are history come alive. and are important to help future generations understand why and how Oregon’s land use planning program had come about with the involvement of so many people.

Governor Tom McCall loomed large in Bill’s mind not just for his call for land use planning but for his vigorous advocacy for Oregon’s Beach Bill and the Bottle Bill, his adoption of an odd-even license plate scheme for rationing gasoline sales during scarcities created by the 1974 oil embargo, and his eloquent insistence on protecting the Oregon coast. McCall had left office in January, 1975, after two very consequential terms in office. Bill wanted to meet him. Thus, in mid-July, Bill, Steve, and I drove in Bill’s green 1969 Volkswagen van to Salem to interview the former governor. We also planned to track down State Senator Hector MacPherson, a chief sponsor of the new statewide planning law.

Despite Bill’s repeated phone calls, McCall had been somewhat vague about an actual appointment. So, in the best traditions of journalism, Bill drove to McCall’s home on Winter Street just north of the Capitol and knocked on the door. After a few moments, the former governor appeared and, knowing he was trapped, graciously invited us in. It was a memorable moment as we sat around the dining room table. Here were two tall affable men, both television journalists – storytellers – in their adopted state of Oregon. One was a former Secretary of State and former Governor, the other would someday be Secretary of State and a candidate for Governor. Both would leave enduring legacies in Oregon. Mcall, when asked, admitted that he missed the tumult and give-and-take of the capitol. “I circle it hungrily each day” he said.

Later that day, we drove to a grass seed field off Oakville Road, south of Albany, where we found State Senator Hector MacPherson on his tractor working his fields. Standing under a hot sun next to the tractor, Steve videotaped the plain-spoken farmer as he and Bill talked about what compelled him to propose this law, why it was so important and what he hoped it would accomplish.

In retrospect, I believe these two interviews were foundational to Bill’s future aspirations for public office. Bill was not awed by either man; he was completely comfortable asking questions and engaging with them. These interviews showed him that the political process was accessible to virtually anyone and could, in fact, affect Oregon’s future in ways that resonated with his own convictions.

By mid-1976 I had moved to Salem to work on the staff of the new statewide planning agency. Bill remained in Bandon and joined KCBY-TV in Coos Bay as a newsman where he came into people’s homes in Coos and Curry counties several times a day. He also formed his own video production business he dubbed “Local Color” using the latest portable video recording and editing equipment, now in color. When not at KCBY-TV, he set out to find and interview local people who he found interesting, creative, and colorful and to then tell their stories in two-to-three-minute video segments.

He scoured Coos, Curry, and Douglas counties and, eventually, further afield to eastern Oregon, Washington, and Idaho. In my work for the state, I traveled frequently to eastern Oregon and so was able to point him to people and situations that I thought he might find interesting. I was able to accompany him from time to time as his audio assistant such as when he interviewed a pea farmer near Boardman, a rancher in the shadow of Steens Mountain, and a silver mine operator deep in the mountains east of Jordan Valley. One trip, to the tiny town of Kinzua in northeast Oregon, resulted in a three-part series on the closing of the sawmill and the effect it was having on the community. We did not know it then but the Kinzua story was a harbinger of similar stories that would play out across Oregon in the coming decade.

Even though these video stories always ended with “This is Bill Bradbury reporting,” they were always about the people in the story, not about him. Today, if you go online to YouTube and search for “Bill Bradbury Local Color,” you will find many of these video stories.

One of his Local Color trips was to Roseburg where, in the Windmill Restaurant, he interviewed a young emergency room physician who had just been elected to the state legislature as a Democrat in conservative rural Douglas County. His name was John Kitzhaber. Bill told me later that the interview first planted the seed in him of running for public office. Kitzhaber had assured Bill that he thought it was entirely possible for Bill to win an election in Coos County. As things turned out, this was the beginning of a life-long friendship between the two that was cemented over the years not just by political collaboration but by days and weeks spent together rafting the wild rivers of Oregon and Idaho, thrilling to the splash of cold water in countless rapids, sitting around campfires deep into the night, soaking in the rivers’ magic beneath the stars.

Local Color, while enjoyable, did not really pay the bills, and so Bill took a job with KVAL-TV, the NBC station in Eugene where his news broadcasts reached all southwestern Oregon through affiliates such as KCBY-TV in Coos Bay. He then moved to Portland in 1978 as a newsman at KGW-TV, also an NBC station, where Tom McCall had once worked and would soon return as political commentator. On KGW, Bill’s news stories came into homes all over Oregon.

On a personal note: In November of 1979, while he was living in Portland, Bill accompanied me to the hospital to attend the birth of my son, Jules, who, years later, worked on Bill’s political campaigns before himself being elected to the state legislature. True to his journalistic instincts, Bill photographed the entire event.

By the summer of 1979 Bill resolved to return to Bandon to run for the Oregon legislature and to be near his two young daughters, Abby and Zoe. He sought out Peter Toll, a long-time friend in Bandon with local political experience, to be his campaign manager. With Peter’s assistance, encouragement, and frequent blunt advice, Bill won a tough Democratic primary campaign then in November 1980 easily won the general election, including strong support in rural Republican-dominated precincts. Thus, at the age of 31 and after living in Bandon for a little more than eight years, Bill went to Salem to represent the people of southern Coos and Curry counties, House District 3, in the Oregon legislature. He was on his way.

_________________________________________

In Salem, Bill made an immediate impact in the House of Representatives, first by his presence, his huge laugh and charisma. Even as a freshman he stood out and people gravitated to him. Second, the legislation he championed was for real things his district cared about, most notably creating the Salmon-Trout Enhancement Program – STEP – that assists landowners and citizens in protecting and enhancing fish habitat. More than 40 years later, STEP continues to be a successful and popular program administered by the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife.

In 1980, about the time of that first legislative campaign, Bill received a diagnosis of Multiple Sclerosis (MS) that caused him to reevaluate and alter many aspects of his health and diet. He became a student of MS and worked hard through diet (e.g. no cheese!), exercise, and acupuncture to stave off its symptoms. He was determined that this condition would not interfere with his life. In 1984, when he ran for the State Senate, he announced his diagnosis publicly because he thought his constituents deserved to know of his condition, which caused him to walk awkwardly at times, directly from him. He did not want anyone to think he had been drinking. It never became a political factor when he ran for office.

Over the next 40 years, although the disease wore him down physically, it did not alter the joy and enthusiasm he felt for life. Eventually, as walking became more difficult, he acquired a Segway stand-up scooter to enable him get around. He installed a power lift device inside the hatchback of his car to enable him to load and unload the heavy machine. The Segway added another six inches to his height and he cut a towering figure in the state capitol building and on the streets of Salem as he zoomed along, usually with a hearty “Whoo Hoo!” to those he passed. River rafting, kayaking, and, later, sailing, offered a way for him to experience and enjoy the outdoor environment which he deeply treasured.

After two terms in the House, he ran for a vacant state Senate seat and, again after a tough Democratic primary, easily won the general election with broad Republican support. In early 1986, a year in which he was not running for re-election to the state Senate, he ran for Congress when Democrat Congressman Jim Weaver retired.

As Bill planned his campaign for Congress, I was mindful of our airplane experience over the foggy Umpqua River as well as the October 1947 crash of a small airplane north of Klamath Falls that killed Oregon Governor Earl Snell, Secretary of State Robert Farrell, and State Senate President Marshall Cornett. I told Bill that whatever he did, he was not to fly in a small airplane to campaign events across rugged, remote mountains in the far-flung Fourth Congressional District in anything less than clear, calm weather. I did not want him to be a headline for the wrong reason! He lost a close three-way primary election to Peter DeFazio, then a Lane County Commissioner, who went on to be elected and serve thirty-eight years in the U.S. House of Representatives.

That summer, on a sunny and only slightly windy day, Bill and Katy Eymann exchanged wedding vows as they stood a few steps from the edge of a cliff on the ocean’s edge at Shore Acres State Park. Their backdrop was an enormous upturned sun-bleached “rootwad” of a windblown ancient Sitka spruce. Katy, then an attorney in Coos Bay, was from a family steeped in Oregon politics; her father was a state representative for several terms and served as Speaker of the House in the early 1970s. Bill and Katy eventually built a house in Bandon not far from the site of the old Two Season’s restaurant, in view of the ocean, that was their permanent home even though from time to time, they resided elsewhere as Bill’s political life unfolded. Years later, as his MS increasingly affected his mobility, Katy became his constant companion, assisting him in his travels and participation in events.

In his role as state Senator, Bill and I continued to confer on coastal or ocean issues. For several years, my work for the state had focused on proposals by the Reagan Administration to lease the seafloor off the Oregon coast for offshore oil and gas drilling and for marine mineral mining. As Bill learned the potential for harm to the marine and coastal environment, he became a steadfast, articulate opponent of these proposals. He organized legislative colleagues from California, Washington, Alaska, and Hawaii to form an Ocean Resources Committee of the Western Legislative Conference to coordinate state responses throughout the region. He was also deeply concerned about proposals by Secretary of the Interior James Watt and the Reagan Administration to explore for exotic minerals on the seafloor in deep waters off the southern Oregon coast, a proposal mostly meant to convince the Soviet Union that the United States was capable of supplying itself with so-called strategic minerals critical to the defense industry. Eventually, neither oil and gas drilling or mineral mining would be activated but at the time the proposals felt real and threatening.

Alarmed by the possible new threats to the ocean, Bill wanted to strengthen Oregon’s ability to protect state ocean waters over the long term. He was determined to introduce legislation to put Oregon on firmer footing and because I had been working with various state and federal agencies on these ocean issues, asked me to help him think through what ought to be in the bill. We worked with the Office of Legislative Counsel over several months to write legislation and gain support from state agencies who would be charged with carrying out the new law. In early 1987, as the Senate Majority Leader and with John Kitzhaber as Senate President, Bill introduced Senate Bill 630, creating the Oregon Ocean Resources Management Program, the nation’s first state ocean management program. The bill passed the Senate on a unanimous vote and passed the House with only two votes against. Four years later the law was amended to create the Oregon Ocean Policy Advisory Council and require a Territorial Sea Plan, both of which have become fixtures in Oregon’s management and protection of its ocean resources.

Over time, this law inspired similar legislation in California, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, and other states which, in turn, became the foundation for an Executive Order on national ocean policy from President Obama in 2010. In fact, it was while on a trip to Washington, D.C. in early 2008 to speak about state ocean planning to the Coastal States Organization, for which I was Oregon’s delegate, that he got the phone call from Hillary Clinton in the Chicago airport seeking his support at the upcoming Democratic national convention. We would never have guessed that our friendship begun over a beer on Bear Creek and honed in a house overlooking the ocean would someday have effects across the country.

In 1995, after Republicans gained a majority in the state Senate and dominated the session, Bill resigned his seat to found a non-profit organization he called “For the Sake of the Salmon.” Here, he felt he could make more progress in that arena working with federal, Tribal, and state natural resource leaders in all three West Coast states to protect these fish and their habitats. For the Sake of the Salmon created a tri-state program to build capacity in local watershed organizations to work with landowners to protect and restore salmon habitat. It also created salmon-friendly power-purchasing programs for utility customers, communities, and organizations.

But public office came calling again in late 1999 when Oregon Secretary of State Phil Keisling resigned. John Kitzhaber, by then Governor, embraced Bill as “the Big Chinook” when he appointed Bill to serve as Oregon’s 23rd Secretary of State. Bill served the remaining 14 months of Keisling’s term, then ran for and won re-election in 2000 and again in 2004. His Constitutionally-limited term ended in early 2009.

During those nearly ten years as Secretary of State he had a chance to stretch his wings and take on many tasks that spoke to his early instincts to work for justice and equality. Most notably, he became an enthusiastic champion of Vote-by-Mail and poured himself into implementing Measure 60 enacted by citizen initiative in 1998 that mandated Vote-by-Mail as the election process at all government levels in Oregon. He was proud that, as a result, voter participation went up and voter fraud went down. He became a missionary for Vote-by-Mail and was always mystified by the reluctance of other states to adopt such an easy and common-sense approach to improving voter participation. He also initiated an on-line reporting system called ORESTAR that, to this day, provides the public with easy access to information about contributions to political campaigns in Oregon.

In 2002, while mid-term as Secretary of State, he ran for the U. S. Senate against Senator Gordon Smith, the Republican incumbent who had replaced him as state Senate President in 1995. My son, Jules, whose birth Bill had attended 23 years earlier, accompanied him on campaign travels across the state. Bill lost but remained Secretary of State. In 2010, unable to seek another term as Secretary of State, he ran in an open primary for the Democratic nomination for Governor against, among others, his friend John Kitzhaber who was seeking to return to the office to succeed Governor Ted Kulongoski.

Bill lost. He was no longer an elected official. But he still had work to do.

As the years rolled by, Bill had seen and heeded the signs of a new threat to the environment and had become an early and tireless advocate for informing the public about the on-coming effects of Earth’s changing climate and the need to take action to reduce the causes and effects. Even while Secretary of State he traveled to Tennessee for training in climate change education led by former vice-president Al Gore. Over the next ten years or so and despite increasing limitations from his MS, Bill and Katy traveled the roads of Oregon in their hybrid vehicle visiting large towns and small communities, in time giving hundreds of talks sounding the alarm over the prospects of climate change and steps that he saw as necessary to protect Earth’s environment. More than forty years earlier, he had traveled many of those same roads to video record community discussions about land use planning. Now he returned to talk about the future of those communities and the entire planet.

In early 2011, outgoing Governor Ted Kulongoski appointed Bill as one of Oregon’s two members of the Northwest Power and Conservation Council, a multistate organization that develops and oversees a region-wide power plan and associated fish and wildlife conservation measures. This was a great fit for Bill’s interests, experience, and skills. He served as chair in 2013 and 2014 where he continued to advocate for salmon, energy conservation, and ways to reduce or avoid impacts of climate change. He left the Council in 2018.

For the first time in nearly four decades Bill was a civilian again with no title, no specific role to play. But, of course, that had never stopped him! There was no shortage of causes to pursue and ways to stay active and engaged. And so, in early 2018 he and Katy drove to Salem where, sprinkled by a light rain, he gave a rousing speech on the steps of the state Capitol to a crowd protesting an LNG (Liquified Natural Gas) export terminal proposed for the shores of Coos Bay, not far from his beloved South Slough. Later that same day, he and Katy joined an “illegal sit-in” in Governor Kate Brown’s ceremonial office to the protest the LNG project.

He was tickled to accept my invitation to serve on an advisory council for the Elakha Alliance, a non-profit I had organized in my retirement to return sea otters to the Oregon coast. In 2018 Katy decided to challenge an incumbent for a seat on the Coos County Board of Commissioners. Over the next two years, Bill was her counselor and cheerleader. Although Katy pursued a vigorous grass-roots campaign, the incumbent won in 2020.

Despite Bill’s enthusiasm and energy, his attitude of “damn the torpedoes, full speed ahead” and the admiration of friends for his courage and perseverance, MS continued to silently, inexorably, tighten its grip on his body. It never released that grip, not for a moment. It was no longer just that his legs did not work properly or that his balance was unsteady. His hearing diminished and even his speech was affected, especially when tired. His hands did not work the way they used to. There were times I could tell that he really wanted to be “present“ and be engaged in a room or in a crowd but simply had to sit back and watch, always smiling.

River rafting trips, which over the years had enabled him to get out and immerse himself in the wild outdoors of the Pacific Northwest, were no longer feasible. The physical effort required was simply too much. In their place he and Katy went on sailing trips in Puget Sound, the Caribbean, and the Mediterranean where adventure could be had but so could the support systems he increasingly required.

One adventure remained: an around the world cruise. He and Katy did their research, made the arrangements, and embarked in San Francisco in mid-January 2023. His MS went with them.

_____________________________________________

When I first met Bill, we did what young people did at the time to find common ground – we compared our record collections and played for each other songs or entire albums that were important to us. One of his songs stood out. It was entitled “Simple Gifts,” subtitled “A Shaker Hymn.” I recognized the tune from Aaron Copland’s suite Appalachian Spring but did not realize there were lyrics for it. “Yes,” he said, “I like this song and its words. They speak to me. They center me.” He explained that while the traditions and practices of the Shakers and Friends (Quaker) are separate, the words expressed some of the Quaker world in which he had grown up. The song was written in 1848 by Elder Joseph Brackett, Jr.

‘Tis the gift to be simple, ‘tis the gift to be free,

‘Tis the gift to come down where I ought to be;

And when we find ourselves in the place just right,

‘Twill be in the valley of love and delight.

When true simplicity is gained,

To bow and to bend we shan’t be ashamed,

To turn, turn will be our delight,

Till by turning, turning we come ‘round right

I don’t know that we ever spoke of it again. But over the years I could see these words play out in the way Bill lived his life and the way in which he involved himself in the “the valley of love and delight.” His friends celebrating his life in October of 2023 sang this song. Bill had indeed “come ‘round right.”

(Here is a link to Judy Collins’ version of “Simple Gifts,” which may very well be a version that Bill heard in the late 1960s. Some of Bill’s interviews can be seen on his “Local Color” YouTube channel.)

Robert (Bob) Bailey returned from college to his native Coos County in 1971, just in time to meet Bill Bradbury. He spent most of his professional life working on coastal and ocean issues for the Oregon Dept. of land Conservation and Development. Today he is the board president of the Elakha Alliance, an Oregon nonprofit with a mission to return sea otters to the Oregon coast. He also plays guitar with friends.

Comments, thoughts or questions? Email us now!