Climate Action is Good for Health

Historically, when Americans hear “climate change,” we imagine a polar bear struggling on ever-shrinking ice. But our perceptions are beginning to shift: we may now be as likely to envision people suffering while working in the heat, fleeing wildfires, wading flooded streets, and checking their children for ticks. People are being affected – your parents, grandparents, and especially your children and grandchildren. These impacts are increasingly on the minds of those in medicine and public health.

Reports keep coming in focused on climate change and health. One was the 2018 global Lancet Countdown on Health and Climate Change; 1 another was the accompanying Lancet Countdown Brief for the United States.2 A third was the 4th U.S. National Climate Assessment, which contained a standalone chapter on human health and included health in the sectoral assessment chapters. The reports all present the same key messages: climate change is here, it is bad for your health, immediate actions can reduce future risks, and climate action has immediate and substantial health benefits. In short, climate action is good for health, and it’s time.

Climate change

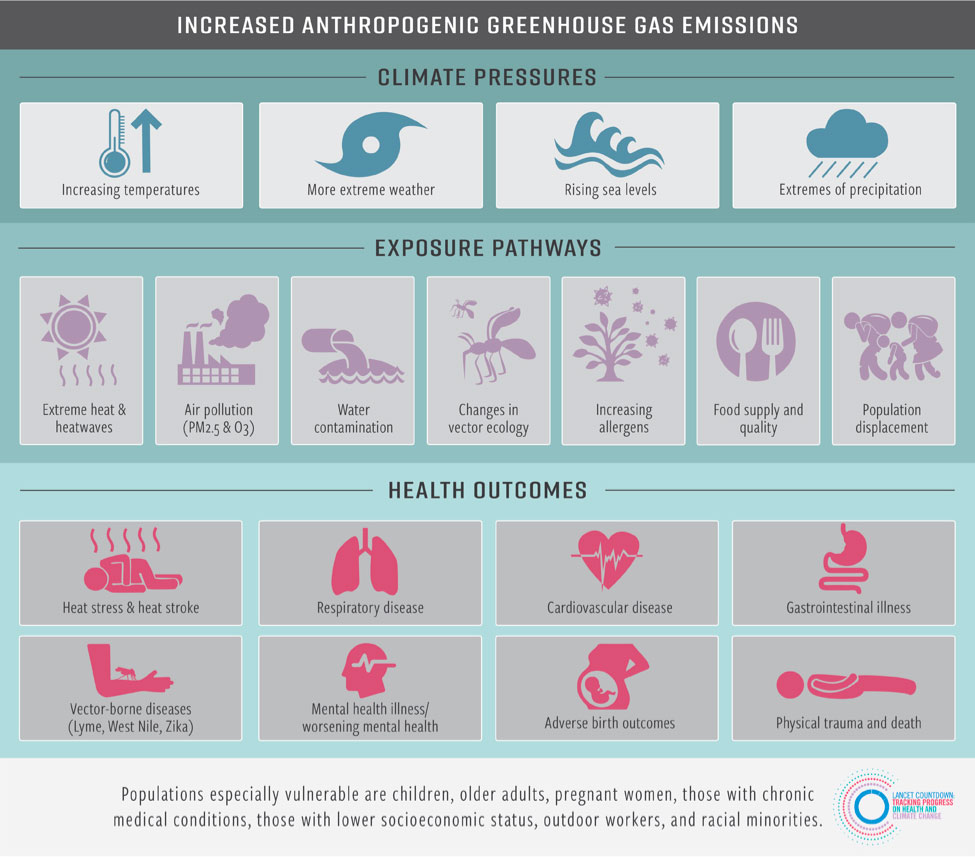

Climate change has warmed the world by roughly 1.8 degrees F, heating the oceans and land alike, melting snow and ice, raising sea levels, and increasing the frequency and severity of extreme weather events.3 Over the course of this century, these changes will accelerate, and sea level rise will become much more apparent. All these changes impact health through a variety of pathways (Figure 1). The pace of these changes has been increasing since the 1970s, and this will continue. Each additional unit of warming is projected to increase the magnitude of health risks.

Figure 1: Summary of the health risks of climate change in the United States.1,4

Summary of selected health risks

Heat: Extreme heat is the leading cause of weather-related deaths in the U.S. Yet each death is potentially preventable. Because of climate change, summers are starting earlier, lasting longer, and are on average hotter. We are regularly setting new records for heat. The average summer temperature in 2016 was 2.2°F greater than the 1986-2005 average, resulting in 12.3 million more Americans exposed to extreme heat that year.

As more Americans are exposed to extreme heat, increasing numbers of people are at risk for heat exhaustion, life threatening heat stroke, and exacerbations of chronic lung, heart, and kidney diseases. One estimate projected that by the year 2050, approximately 3,400 more Americans could die annually from heat alone.

Researchers are continuing to discover new connections between heat and health. Emerging evidence suggests that hotter temperatures increase antibiotic resistance, worsen mental health conditions, increase suicides, and blunt cognition. Exposure to higher temperatures can also cause complications with pregnancy.

Children, pregnant women, outdoor workers, older adults, those who are chronically ill, and low-income families disproportionately suffer more deaths, hospitalizations, and emergency room visits associated with heat. The healthcare costs from one heatwave event alone were estimated at $179 million.

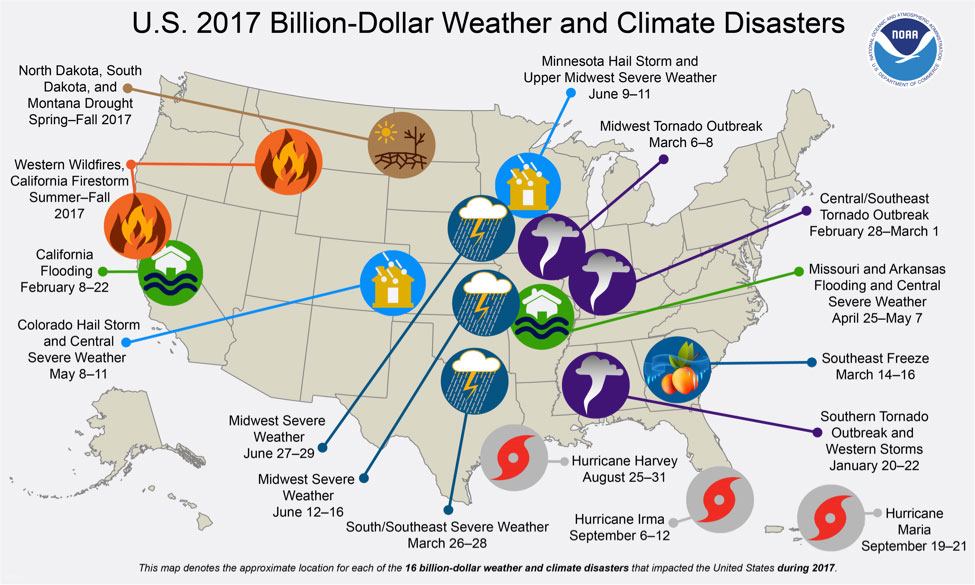

Extreme Events: Extreme weather and climate events, such as floods, droughts, hurricanes, and wildfires, are also increasing, threatening health and healthcare facilities. In 2017, there were 16 disasters in the U.S. that cost over a billion dollars each, some dramatically so: together these events cost about $306 billion dollars (Figure 2). The official death toll was estimated at 3,278, although the actual number is likely much higher. During this same year, 23 events (floods, storms, wildfires) affected approximately 866,835 individuals. The homes of 109,108 individuals were destroyed.

Since 1980, overall damages from 219 weather and climate disasters in the U.S. exceeded $1.5 trillion.

The historically destructive 2017 wildfire season, which burned 9.8 million acres and killed at least 44, was a dramatic display of the potential consequences of climate change. Wildfires are expected to become more common as the climate continues to change. This means more Americans could be affected by the dangers of exposure to the fine particles and ozone precursors in wildfire smoke that can harm the heart and lungs.

Each region of the country experiences extreme weather, with the impacts often felt well beyond the affected area – whether it is wildfire smoke impacting air quality states away, cities caring for the displaced, or hospitals facing a lack of critical supplies. Those most affected by these events are the most highly exposed, the poor, the chronically ill, and children and older adults.

Figure 2: U.S. 2017 Billion-Dollar Weather and Climate Disasters.5

Infectious diseases: Multiple infectious diseases are transmitted by mosquitoes, ticks, and fleas, such as Lyme disease and West Nile virus. Warmer weather is increasing the locations where these insects are found and their numbers; the number of cases of these climate-sensitive infectious diseases tripled between 2004-2016.

Research can project where these insects and the diseases they can carry may appear in the future. For example, warmer water temperatures during longer summers support the growth of bacteria called Vibrios that can cause diarrheal illnesses, food poisoning, and skin infections. In the Northeast, there was a 27% increase in the coastline area suitable for Vibrios in the 2010s vs the 1980s. This means more Americans could be at risk through contact with the water or through eating contaminated shellfish.

Air quality: Poor air quality causes a host of health complications, with climate change multiplying the threats. Climate change is decreasing air quality by increasing concentrations of ground-level ozone, which harms the lungs and can cause early death.6 Earlier springs, warmer temperatures, precipitation changes, and higher carbon dioxide concentrations can increase exposure to airborne pollen allergens that can be especially harmful to those with hay fever and asthma. In addition, while air quality across the U.S. improved since 1988, it has been deteriorating in western states because of wildfires.1

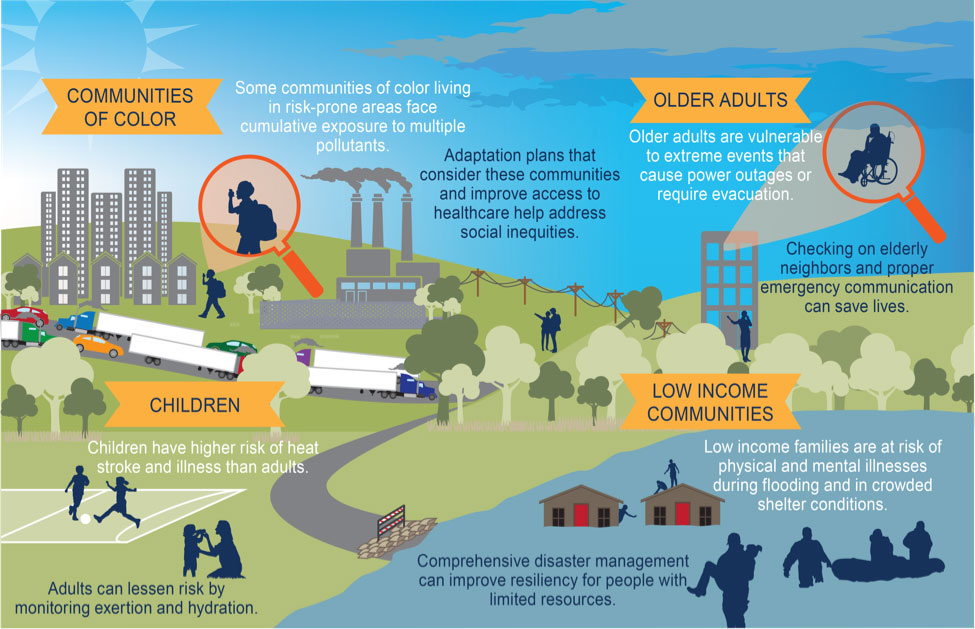

Climate change disproportionately affects the vulnerable

There is wide variability in which communities are exposed to which climate-related hazards. Certain populations are particularly susceptible to the changing weather patterns associated with climate change (Figure 3). These populations can be proactively protected and strengthened through a range of interventions, as noted in the figure.

Figure 3: Populations particularly vulnerable to climate change and actions to increase resilience.7

Protecting health and saving lives

Actions to prepare for and manage the health risks of climate change are two-fold:

- Reduce greenhouse gas emissions from coal-fired power plants, vehicles, and other sources. While the energy system’s carbon intensity is decreasing with more low-carbon electricity production, it needs to happen faster. Most policies to reduce emissions also have health benefits for the health of Americans in the near and long term. The 4th U.S. National Climate Assessment concluded that “by the end of this century, thousands of American lives could be saved and hundreds of billions of dollars in health-related economic benefits gained each year under a pathway of lower greenhouse gas emissions.” Renewable energy sources such as solar and wind are increasingly affordable and are associated with cleaner air and water.

Our health care systems, which consume significant amounts of energy, should take the lead, powering operations with renewable energy sources. This would allow healthcare systems to model health protection in our changing world. Individual action is also important, like walking and biking instead of driving for short trips, which both improve health and reduce emissions.

- Take proactive measures to minimize climate change health impacts and prevent disruptions to healthcare services. Targeted policies and programs are needed to protect vulnerable populations. And healthcare systems must become more resilient. For example, in coastal regions, many hospitals and clinics are located in areas subject to flooding, as was witnessed in Houston, Miami, and Puerto Rico following hurricanes in 2017. This also is true in many other coastal communities. Mapping which hospitals may be subject to various levels of inundation is an important step.

Conclusions

The health impacts of climate change are becoming increasingly felt and the health benefits of climate action are abundantly clear. While there are a large number of actions communities, states, and federal agencies can undertake to protect and promote the health of communities in a changing climate, individual action is still important. Climate action is good for health and needs to start now.

References

- Watts N, Amann M, Arnell N, et al. The 2018 report of the Lancet Countdown on health and climate change: shaping the health of nations for centuries to come. The Lancet [Internet] 2018 [cited 2018 Dec 3]; Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0140673618325947

- Salas R, Knappenberger P, Hess J. 2018 Lancet Countdown on Health and Climate Change Brief for the United States of America [Internet]. London, United Kingdom: Lancet Countdown; 2018. Available from: http://www.lancetcountdown.org/media/1426/2018-lancet-countdown-policy-brief-usa.pdf

- Wuebbles D, Fahey D, Hibbard K, Dokken D, Stewart B, Maycock T. Climate Science Special Report: Fourth National Climate Assessment, Volume I [Internet]. Washington, DC: U.S. Global Change Research Program; 2017. Available from: https://science2017.globalchange.gov/

- Figure 1 created for Lancet Countdown Brief for the U.S. For additional information see: http://www.lancetcountdown.org/media/1426/2018-lancet-countdown-policy-brief-usa.pdf by M. Lee (Climate Nexus)

- Figure 2 denotes the approximate location for each of the 16 billion-dollar weather and climate disasters that impacted the United States during 2017. For additional information from NOAA, see https://www.climate.gov/news-features/blogs/beyond-data/2017-us-billion-dollar-weather-and-climate-disasters-historic-year

- USGCRP. Impacts, Risks, and Adaptation in the United States: Fourth National Climate Assessment, Volume II [Internet]. Washington DC, USA: U.S. Global Change Research Program; 2018 [cited 2018 Dec 3]. Available from: https://nca2018.globalchange.gov/

- Figure 3 from 4th US National Climate Assessment https://www.globalchange.gov/nca4 For additional information, see https://www.globalchange.gov/nca4

Authors

Kristie L. Ebi, Ph.D., MPH

Director, Center for Health and the Global Environment

University of Washington

Seattle WA

Jeremy J. Hess, MD, MPH

Co-Director, Center for Health and the Global Environment

University of Washington

Seattle, WA 98105

Renee N. Salas, MD, MPH, MS

Burke Fellow & Affiliated Faculty, Harvard Global Health Institute

Clinical Instructor in Emergency Medicine, Harvard Medical School

Department of Emergency Medicine, Massachusetts General Hospital

Boston, MA

Comments, thoughts or questions? Email us now!