Returning Sea Otters to Oregon: Repairing a Torn Fabric

The ocean along the Pacific Coast is exhibiting unmistakable signs of stress as the result of a changing climate and pressures from other human activities. Increasingly acidic ocean water, caused by an over-abundance of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere and in ocean waters, is affecting calcium-based marine life such as very young crab and oysters. Ocean heat waves have changed the mix of plankton, driving down the biologic productivity at the base of the marine food web and affecting the diets of sea birds, salmon, Orcas, and other cold-water species. High levels of domoic acid and toxic algal blooms that affect crab, clams and other marine life have likely been exacerbated by the warmer water discharged from coastal streams laid bare to the sun after fierce wildfires destroyed streamside trees.

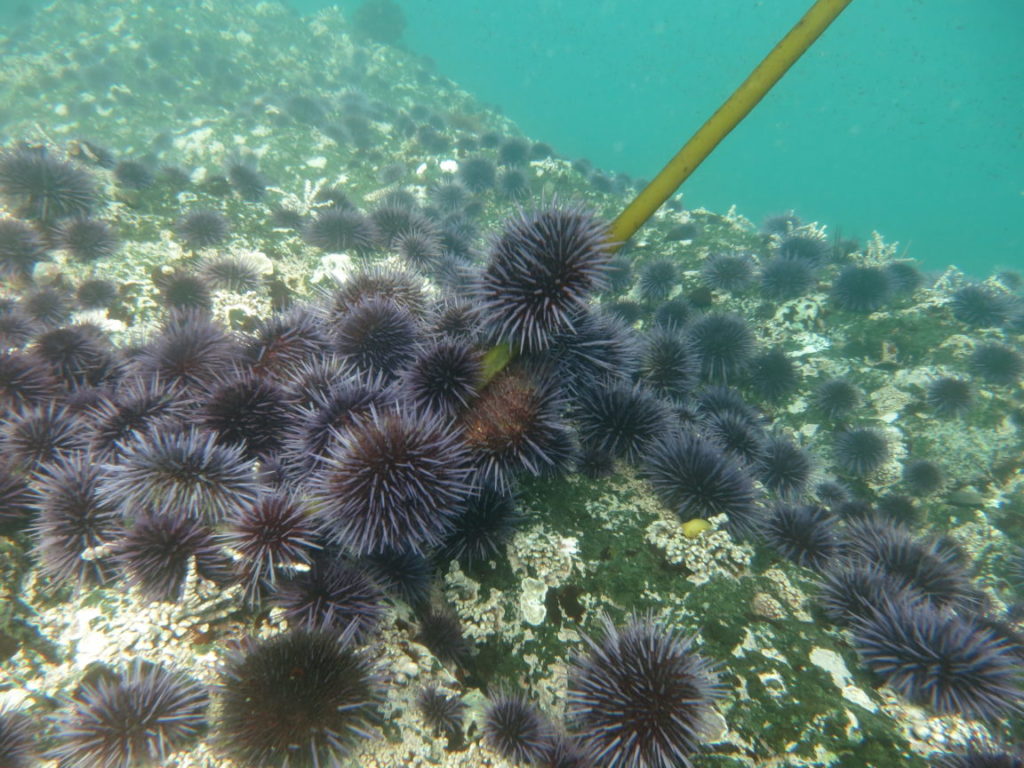

Perhaps the most tell-tale sign is the disappearance of kelp forests due to the unchecked spread of sea urchins. A perfect storm of factors contributes to this plague of urchins: a massive die-off of sea stars, an urchin predator, from a mysterious wasting disease; increasingly warm ocean water that degrades the health of kelp forests; and a massive “recruitment” of baby sea urchins in 2014 that have now grown to maturity. But behind these factors is the absence of sea otters.

A few miles north of Newport, one of Oregon’s major fishing ports and a center of marine science, is Otter Crest, a viewpoint high on rugged Cape Foulweather that offers a spectacular view of the Pacific Ocean to the west and the coastline off to the south. The cape was so named by Captain James Cook in 1778 to denote the miserable day he first sighted land on the northwest coast of what the British referred to as New Albion. This was Cook’s third voyage into the Pacific Ocean, long claimed by the Spanish, and his mission was to find a Northwest Passage between the Pacific and Atlantic oceans. So he explored, carefully observing and mapping the shore as he went.

Cook never found a Northwest Passage. But what he found in the Aleutian Islands far north of Cape Foulweather was of immense consequence to the world. On those windswept, remote islands, he and his crew found the most distant outposts of the Russian Empire, where native Aleut hunters harvested sea otters for what would turn out to be a very lucrative trade with China. The hunt for the lush fur pelts of sea otters set off a chain of events that, over the next century, fueled a global race for wealth among the great nations, reshaped the map of North America, and changed forever the lives and culture of coastal Indian people. Moreover, it brought to the brink of extinction the most ecologically important animal in the coastal ocean.

The coast of Oregon did not escape these events. We know sea otters were here – and they are not now. About two miles south of Otter Crest and a quarter mile offshore, is a non-descript rock fringed by white foam. Known to Tillamook Indians as əs·hí·higəl ʃə́·nʃis (us-HII-hi-gul SHUN-shis), literally, Otter Rock, this modest rock is today officially named Otter Rock and is the namesake of a no-take marine reserve area designated by the State of Oregon. About one hundred sixty miles further south near the mouth of the famous Rogue River is a rocky point of land referred to by Tututni Indian people as xvlh-t’vsh see (XUTL-tush sae), literally Otter Rock. Today it is known as Otter Point.

Today, the only sea otters that live in Oregon are in large tanks of sea water at the Oregon Coast Aquarium in Newport and the Oregon Zoo in Portland where they eat restaurant-grade seafood doled out from plastic buckets. But if they were once here, as the names of Otter Rock and Otter Point suggest, why are they not now? Why are they found in Alaska, on Washington’s Olympic Coast, and along the central California coast but not on the seemingly wild Oregon coast? Could sea otters return to Oregon and if so, how?

These are not the only questions to be asked. Perhaps the most fundamental question is whether it even matters that they are missing. The marine environment on the Oregon coast seems pristine and productive, so why should we even care? But in considering their return, other questions arise: can what has been lost truly be regained? Can a fabric once torn be mended? How do we weigh the importance of a species that is absent from living memory? Fundamentally, what do sea otters have to do with all of us?

One set of answers relates to the critical importance of sea otters to the overall health and diversity of northeast Pacific marine and coastal ecosystems. These answers point to the ways that the complex ecological fabric of Oregon’s nearshore and estuarine ecosystems has likely been affected by their absence.

A second set of answers relates to loss of the ancient cultural connection between coastal Indian people and sea otters. How were these relationships between sea otters and Indian people woven into the fabric of ancient lifeways and knowledge of place?

Finally, the return of sea otters to other coastal areas once occupied by their ancestors teaches us why we should care that these animals are missing. Their return elsewhere clearly points to what surely has been lost in Oregon as well as what might be gained from their renewed presence.

Once Upon a Time

For about five million years, sea otters of the genus Enhydra lived along the edges of the great ocean currents across the North Pacific Rim. They ranged from the island of Hokkaido, Japan, northward past the Kamchatka Peninsula of today’s Russia, across the long chain of Aleutian Islands, along the complex coasts of Alaska and British Columbia and southward along the relatively straight coast of the United States nearly to the tip of Baja California in Mexico. It is thought that, in total, about 300,000 animals populated this 6,000-mile arc although no one was counting.

When humans first ventured eastward from Asia to North America near the end of the last Ice Age some 20,000 or so years ago, sea otters were there to greet them. Some scientists speculate that early people may have made their way southward along the coast via a “kelp highway” of relatively protected water, moderate temperatures, and rich food resources. At that time, sea level was much lower so the coastline known to early people and sea otters was different than the one we know today. As glaciers melted and sea level rose, this coastline moved imperceptibly landward, changing in response to the geology it encountered. Evidence of these ancient shorelines now lies covered by several hundred feet of today’s Pacific Ocean.

Archaeological evidence clearly shows that for at least the last 5,000 years, sea otters and humans lived together on the Oregon coast. Bones of sea otter are the second most numerous marine mammal bone found in middens, the piles of shells, bones, and other debris created near villages or encampments of Indian people. A nearly intact sea otter skeleton was recovered in 1983 from an archaeological site in Bandon, Oregon, at the mouth of the Coquille River. Such ancient bones and teeth can provide the material for sophisticated modern genetic testing to help determine the deeper history of sea otter populations on the Pacific Rim.

These lithe, intelligent animals would have certainly made an impression on the humans who encountered them throughout their range. The diverse indigenous peoples of Oregon’s long coastline are no exception. Although often recorded a generation or more after sea otters’ extinction in Oregon, the testimonies of coastal Indian elders to 20th century historians and ethnographers are alive with the presence of sea otters. These stories range from casual recollections to deeply held cultural beliefs.

Annie Miner Peterson, a Hanis Coos elder, being interviewed by Melville Jacobs, an anthropologist. Photograph courtesy of Peter Hatch

On one level, sea otters were of eminently practical importance for Indian people. Sea otter pelts, with their beautiful lush fur, provided extraordinary warmth. Luxurious robes made from them stood as a marker of prosperity and distinction. As gifts, these sumptuous robes helped bind up diplomatic disputes and aided prospective grooms striving to impress the parents of their intended.

Each coastal language had a unique word for sea otter, demonstrating their presence everywhere along the entire coast. But certain places stand out as special. Some recollections of elders reveal the old hunting places of family members past, individuals renowned for taking the fast and wary otters by canoe or from offshore rocks or cliff-top redoubts. Accordingly, these spots correspond closely to the places biologists expect would be the best habitats for sea otters in the present day.

Other stories tell of a time when the boundaries between the human and animal, the earthbound and spiritual worlds stood more porous than today. These stories communicate other levels to the presence and importance of sea otters. In story after story the reward to various mythic protagonists, whether obtained by virtue, luck, or guile, comes in the form of fabulous numbers of sea otter pelts. Still other stories relate events that instruct the listener to view sea otters as kin, and explain the relationship between humans and sea otters as inextricable from the bounty of resources provided by the ocean on which our fleeting human lives depend. In this way, these old understandings prefigure new ones slowly being revealed by contemporary ecological science.

A Special Creature

Sea otters occupy a magic zone in shallow ocean waters where sunlight penetrates to the seafloor. In combination with cold, nutrient-rich waters, sunlight promotes almost unbelievably lush growth of all manner of marine life based on tiny plants, phytoplankton, as well as many species of so-called seaweeds or macroalgae some of which may be seen covering the rocks at low tide on Oregon’s rocky shores.

Among macroalgae are many species of kelp including those that anchor to the rocky bottom and can grow up to 80 to 100 feet to form a dense canopy of leaves near the surface. Other shorter species never reach the surface, creating a subcanopy, while still others form mats that coat rocks to which they anchor. Together, these macroalgae form a forest in the sea that serves as the engine for a highly complex and biologically productive marine ecosystem. And sea otters are key, literally, to that productivity.

The largest member of the weasel family, sea otters are an unorthodox mammal in a chilly marine environment. Unlike whales or even seals, they are small, not much larger than a German shepherd dog. And unlike whales, seals, or other marine mammals, they have no insulating fat or blubber. Instead, distinctive characteristics keep them warm. One, they burn an enormous amount of caloric energy to keep their metabolic furnace roaring, consuming about twenty-five to thirty percent of their body weight in food every single day. The second is an extremely dense coat of fur, with up to a million hairs per square inch, that keeps their internal heat from draining away into the cold ocean.

To obtain this caloric energy, sea otters have developed some specialized characteristics. Elongated lungs enable extended foraging time underwater. Large, webbed hind feet provide speed while dexterous front paws, padded against sharp sea urchin spines, can grasp and carry prey. A pouch in the loose skin of the armpits enables them to carry multiple food items or, frequently, a rock to the surface. To conserve energy while diving, sea otters target shellfish such as sea urchins, clams, and snails that don’t move although they will capture such mobile prey as crab and octopus.

Once at the surface, a sea otter will float on its back, hold its food item in its front paws and use powerful jaws and flat crushing teeth to break open the shell and access the flesh inside. If necessary, a sea otter will place a rock on its tummy as an anvil and then vigorously smack the hard shell of a clam or other creature against the rock until it cracks open. Then teeth and jaws take over. Because a sea otter always eats at the surface while on its back, sharp-eyed scientists can use powerful spotting telescopes to identify and measure exactly what, where, and how much a sea otter eats.

Sea otters have a profound effect on the kelp forests they inhabit because of their taste for the fatty, caloric-rich reproductive organ (dubbed uni) of sea urchins. These spiny, pin-cushion animals come in several colors and sizes and are surprisingly mobile, hunting and feeding on kelp and other macroalgae. By eating them, sea otters keep sea urchin numbers in check, thereby protecting and enabling kelp forests and the life that depends on them to flourish. Conversely, when sea otters and other urchin predators such as seastars are absent, sea urchin numbers can increase dramatically. They are capable of devouring every blade and stalk of seaweed in sight, resulting in “urchin barrens”, a moniker that aptly describes a sea floor barren of marine life except for a carpet of mostly purple sea urchins.

This key relationship between sea otters and kelp was first observed by James Estes, then a young graduate student in the early 1970s. Estes went to Amchitka Island in the Aleutian archipelago to monitor sea otter populations during atomic testing being conducted by the U.S. government. But when he also went to Shemya Island, about 225 miles west where there were no sea otters, he immediately saw and understood what a profound difference the presence or absence of sea otters had on the marine environment. His basic discovery, subsequently and repeatedly confirmed through observation and research by him and many others, was that the ecological richness of kelp forests where sea otters were present stood in stark contrast to the ecological poverty of areas without sea otters or, as a consequence, kelp.

Kelp forests are foundational to the biologic productivity of the entire nearshore coastal ocean, whether of perennial Giant kelp (Macrocystis) found on the central California coast or the annual Bull kelp (Nereocystis) found from central California northward into southeast Alaska. These forests shelter clouds of eggs and larvae of fish and invertebrate species that drift into these calm environments and, in turn, fuel a food web comprised of innumerable small fish, shellfish, sea birds and even mighty Grey whales. At least eighteen species of rockfish and other fish are reliant on shelter, food, and protection of kelp forest habitat while several other species, such as herring, use kelp in some part of their lifecycle.

The effects of kelp go beyond just the forest itself. Bits of kelp detritus can drift away in the ocean current, providing food to any number of filter-feeding marine animals far beyond the forest. A rotting pile of kelp washed up on the beach is almost immediately beset by insects that attract birds and their predators thereby distributing the ocean’s nutrients far into the terrestrial environment. And, as scientists have recently estimated, kelp pulls an immense amount of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and ocean as it grows, thereby reducing overall carbon in the atmosphere and ocean that contributes to climate change.

Sea otters, with their foundational effect on kelp-forest ecosystems, are now understood to be a classic example of a keystone species, a species that has a disproportionate effect on the functions and structure of the ecosystem it inhabits. The return of another keystone species, the wolf, to Yellowstone National Park more than two decades ago dramatically – and unexpectedly – demonstrated the ecological reach of such a species as fish returned to streams cooled, shaded and fed by trees and shrubs freed of browsing by elk and songbird numbers soared in the now lush riparian vegetation. Almost assuredly, Oregon’s marine environment would benefit in ways expected and unexpected from the return of this missing keystone species.

And Then They Were Gone

After Captain Cook sighted Cape Foulweather in 1778, he sailed northward in search of a Northwest Passage. He charted parts of the complex Alaskan coastline, passed through the Aleutian Island chain, and crossed the Bering Sea. It was at stops in the Aleutian Islands that he learned that the Russians, with the forced labor of indigenous Aleut hunters, were taking sea otter furs for trade with Chinese merchants via a circuitous route through Siberia. Although Cook was not particularly interested in this trade, the value of sea otter pelts and the potential for wealth was made clear to some of his crewmen. At a stop in Canton, China, a messenger from a Chinese merchant climbed aboard Cook’s ship and saw sea otter robes that the crew had obtained in the Aleutian Islands to use for warmth against the raw North Pacific weather. It did not take long for a trade for these furs to take place, much to the advantage and amazement of the crew.

Although Cook died in a well-known episode on the island of Hawaii, the news of potential wealth in sea otter fur spread once his crew, John Ledyard in particular, returned home. Ledyard championed the idea with merchants in Boston that vast wealth from sea otter pelts awaited on the American northwest coast. It is likely that Thomas Jefferson, then residing in France as the American Minister to the Court of Versailles, was among many who heard about sea otters from Ledyard who was in Britain and France promoting his idea. By the late 1780s, British and American companies had formed and sent ships to exploit this raw wealth. A few years later, President Jefferson tasked Meriwether Lewis and William Clark with investigating the potential wealth of a furs along the Pacific coast as a principal objective of their expedition.

The potential for great wealth from sea otter furs set the stage for often violent and tragic clashes between Indian people, who had furs and were eager to trade, and the fur traders who were disposed to offer as little in trade as possible. This violence often erupted during trading encounters usually because of the inability to communicate, which then spawned subsequent resentment, mistrust, and revenge-seeking. The value of sea otter furs sometimes set tribe against tribe in order to secure the goods offered by ship captains for sea otter pelts. Sea otters had become a commodity and the potential wealth inherent in their pelts proved toxic.

The value of sea otter fur attracted competing interests and inflamed rivalries among European nations and the United States. Russia, with its foothold in Alaska, dreamed of territory and settlements farther south in California. Spain reasserted its claim of ownership of the entire Pacific Ocean even as it could hardly afford to maintain its colonies in Alta and Baja California. England, already advancing its territorial interests across Canada via the Hudson’s Bay Company, worried that Russia would capture the west coast of Canada and stake claims further inland. England and the United States were in tension over the westward expansion of the United States and potential territorial claims of each in the northwest.

American companies, under charter to no government, became de facto emissaries of the fledgling United States as they traded for furs with indigenous people. In 1792, Robert Gray, an American sea captain in pursuit of sea otter wealth on the northwest coast sailed his ship, the Columbia Rediviva, into the mouth of the Columbia River and set anchor, the first ship to do so. This simple act was the eventual basis for the U.S. Congress to claim a national interest in the region.

But even as nations jockeyed for power and territory, the population of sea otters underlying the wealth generated by their fur was rapidly disappearing. By the 1830s, sea otters had been nearly eliminated from San Francisco Bay and the California coast causing Russia to give up its dreams of empire in California. The decline in wealth from furs helped to spur Britain and United States to resolve long-standing territorial claims over the Oregon country in 1846. In 1867 Russia sold Alaska, now bereft of sea otters, to the United States to pay off debt incurred in a war with Napoleon. The age of global wealth from sea otter fur was over.

By 1890, even without mass maritime fur trading or hunting in Oregon, most sea otters on the Oregon coast were gone, killed in small numbers in specific locations by the remaining Indians and newly-arrived Euro-Americans who understood that even a single sea otter pelt could make its owner rich. Tragically, during this same era, most Indian people in Oregon including those living on the coast, were forcibly removed from their ancient lands. Relocated to reservations that would later be reduced in size, reduced again, and eventually dissolved, Indian people were left with no home at all. With the extirpation of sea otters in Oregon and the destruction of a way of life, the deep relationship between sea otters and Indian people became a thing of the past.

In Oregon, only the names of Otter Rock and Otter Point remained. In the blink of an eye, sea otters, which had present on the Oregon coast for tens of thousands of years, were gone.

But the species did not go extinct. In several isolated places in the remote Aleutian Islands, in Alaska’s Prince William Sound, and on the Big Sur coast of California, a few sea otters managed to survive. From these Noah’s Arks and later protected by international treaties and federal laws, sea otters have returned to some, but not all, of their former habitats. Whether by slow natural population expansion, as on the central coast of California, or by intentional translocation of animals, as from the Aleutian Islands to southeast Alaska, Vancouver Island, and the Olympic Coast in Washington, their recovery has taken more than a century. And yet a gap of nearly 800 miles remains between animals on the Washington coast and those on the central California coast. Oregon sits nearly in the middle of this gap.

Thinking About Return

In the late 1990s, Dave Hatch, a member of the Confederated Tribes of Siletz Indians on the Oregon coast, built a small boat and needed just the right name. His search led him to the word Elakha, a word for sea otter derived from Clatsop and Chinook Indian languages. It had been incorporated into Chinook Jargon, a pidgin trade language concocted by mountain men, fur trappers and Indians throughout Oregon country as they traded for furs and other items. He liked the word. It fit his boat. But his quest sparked his interest in sea otters and raised questions of why they were absent, whether it mattered, what could be done.

David Hatch with sea otter regalia at a tribal event.

Photograph courtesy of Peter Hatch

Hatch came to learn that unlike today, when the slide of a species toward extinction is documented by scientists, decried by conservation groups, and shown in heart-rending images on television and in social media, the slaughter of sea otters had been invisible to the world at large. He found that their absence in Oregon had been neither noticed nor understood by scientists thus resulting in a faulty understanding of the baseline ecology of the Oregon coast. He also understood that his Aleut and Hanis Coos ancestors had known and felt the loss of sea otters because they experienced it. It was clear to him that a crucial cog in the coastal ecosystem and in the lives of Indian people had been functionally eliminated even before Oregon achieved statehood. It was time to bring them back.

As he began to articulate and advocate the idea of the return of sea otters to Oregon, he enlisted others to his cause. He named this collective effort the Elakha Alliance.

David Hatch left this world not long after his retirement in 2016. But his idea was picked up by colleagues, friends, and others who had come to agree with his premise that sea otters should once again be part of the Oregon coast, part of the ecosystem, part of the lives of Indian people. What had been an informal organization was legally incorporated in early 2018 as the Elakha Alliance. Its board of directors now includes his son, Peter, as well as other tribal members from the Confederated Tribes of Siletz Indians, the Coquille Indian Tribe, and the Confederated Tribes of Coos, Lower Umpqua and Siuslaw Indians. Other board members have strong backgrounds in science, government, conservation, and the law and all are eager to see his idea to fruition.

As it has turned out, David Hatch’s idea of returning sea otters to the Oregon marine ecosystem was not just a good one but a necessary one. Events in the larger world have brought fresh relevance, if not urgency, to his idea.

The Urgency of Return

Port Orford, near Cape Blanco on Oregon’s remote south coast, endures the wind and embraces the ocean beneath the gaze of Humbug Mountain a few miles to the south. Unlike other fishing towns in Oregon that nestle in the calm waters of an estuary, the harbor at Port Orford hides from the surging ocean in the lee of a jetty of massive rocks built by the U. S. Army Corps of Engineers.

Even with the shelter of this jetty there is no dock at water level at which to tie up a boat. Instead, fishermen returning to port position their boat beneath a towering crane that first lifts boxes full of fish for processing. The crane then hoists the boat out of the water and sets it on a dolly which is rolled to a parking area to await the next trip when the procedure will be reversed. Vessels that go to sea from Port Orford must therefore be small enough to be hoisted but large enough to hold a crew and all the gear necessary for commercial fishing. This unique constraint means that the fleet in Port Orford is mostly limited to day fishing, boats setting out before dawn and returning by evening. Within a day’s reach of this fleet are – or rather, were – the largest and most productive kelp forests in Oregon that teem with rockfish and other species that have supported fishing families and the community for years.

In 2018, researchers from Oregon State University studying Grey whales near Port Orford saw something ominous on the ocean floor just beyond the huge jetty rocks. Where just two years before they had photographed a lush growth of kelp and a dazzling array of marine life, they now photographed an ocean floor nearly devoid of kelp, covered with hundreds of purple sea urchins, some clinging to the last stubs of kelp stalks. Scientists with the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife also reported that acre after acre of the vast kelp forests on nearby reefs were now covered almost entirely by millions of purple sea urchins.

The perfect storm had arrived at Port Orford.

Urchin barrens are not just a short-term phenomenon. Even after consuming all available kelp, sea urchins don’t die. Instead, they undergo a metabolic change in which they can exist in a kind of “zombie” state for years until food, kelp, becomes available. Urchin barrens were first noticed a century ago after sea otters were hunted out in Alaska and in California. Their spread has become alarming during the past decade along the West coast as vast areas, once dense with kelp forests, are now covered only by purple sea urchins. The Elakha Alliance and many scientists believe that any long-term solution to urchin barrens must include sea otters as the agent of change. But even if sea otters returned tomorrow, it would take years for areas now covered in sea urchins to return to productive kelp forests.

Meanwhile, expansion of the sea otter population on the California coast appears to have stalled, unable to expand beyond its current range. For the population to expand into new habitat areas, sea otters must swim either north or south into unoccupied territory. But if there is a barrier at the edge of their current range, the animals will be unable to move into that new habitat. The population will be unable to expand and, within the finite amount of food resources in existing habitat, will soon reach carrying capacity. That appears to be the case in California.

And just what is the barrier preventing range expansion? In a word: sharks! Great White sharks, to be exact. While research on Great White sharks is difficult for obvious reasons, it does appear that there is something of a shark population boom due to an increase in the abundance of seals and sea lions on the West coast. Sharks seem to not target sea otters for food, but as adolescent sharks learn what is food and what is not, they may take a test bite on a sea otter if given the opportunity. Such a test bite is nearly always fatal as evidenced by the number of bitten but otherwise whole sea otter carcasses found on the beach. To compound the problem, Great White sharks seasonally aggregate near the Farallon Islands just north of the current end of the California sea otter population so for sea otters venturing north, there is a constant danger from shark bite. Similar shark bite mortality appears to be a factor at the southern end of the range.

Sea otter conservationists are also concerned about the genetic foundation of the California population. The three thousand or so animals in the current population are all descended from a small pool of ancestors that survived fur hunting in remote areas of the Big Sur coast. Conservationists are interested in strengthening the gene flow between these Southern sea otters and their slightly larger Northern sea otter cousins found in Alaska, British Columbia and Washington. Genetic analysis and close physical measurements of bones and teeth found in middens, shell piles near the sites of coastal Indian villages or hunting camps, show that the Oregon coast was a transition zone between Northern and Southern sea otters. Oregon seems a candidate area where the genetics of the two subspecies could mingle, strengthening the genetic makeup of each.

Will Nature Do the Job?

Is it necessary to actively pursue a restoration of sea otters in Oregon? Occasional single sea otters are seen on the Oregon coast so isn’t it possible that they will return on their own? Fifty years have elapsed since a population was reestablished on the Olympic Coast, a population that is today approaching three thousand animals. Surely a male/female pair, perhaps many of them, will relocate to Oregon.

There are two fundamental reasons why it is unlikely that sea otters will return to Oregon on their own from the Washington or the California populations.

First, unlike river otters that may have a litter of several pups, sea otter females have just one pup at a time. These pups are born naive with almost no ability to survive. Mother sea otters devote nearly all their time and energy rearing the pup until it is able to live on its own after which she will be again impregnated by a male to start the cycle again.

Because a mother sea otter is essentially foraging for two when pregnant, lactating or providing fresh shellfish, she must dive frequently to obtain the calories needed for herself and her pup. As long as she finds the necessary food, she will remain in that area. Only when food becomes scarce will she roam to find a more productive location and even then, only as far as absolutely necessary. Unlike sub-adult males who are free to roam, sub-adult females become pregnant as soon as they are developmentally ready, thus perpetuating this trait of “site fidelity.”

Second, the geometry of the coastal shore determines the potential for a sea otter to find suitable prey and habitat in a new unoccupied area. Unlike a sea otter mom in southeast Alaska with multiple habitat options in all directions among the many coves, islands, rocks, and fiords, a sea otter mom in Washington or California has only two choices: north or south. Her choice may be further limited if the adjacent area is occupied and she is forced to keep swimming to find suitable habitat. A sea otter mom and her pup swimming south from the Olympic Coast would need to navigate nearly 130 miles of ocean along the sandy shore to reach the nearest suitable rocky habitat at Cape Lookout. Even better habitat at Cape Arago would be another 145 miles of swimming.

The likelihood of a sea otter pair migrating to Oregon from the population in California is even more remote. It is more than 400 miles from the northern end of the California population to Oregon. Even if animals do make it past the shark barrier north of Santa Cruz and move further north, it is highly unlikely that they would pass up the many habitat opportunities that they would encounter much closer to their current home such as San Francisco Bay, once home to thousands of sea otters, or waters around Point Reyes.

Translocations of sea otters to areas they formerly occupied have often been successful. In the early 1970s several hundreds of animals were taken from harm’s way on Amchitka Island in the Aleutian Islands and relocated to southeast Alaska, to Vancouver Island, and to the Olympic coast of Washington. These animals were the basis of today’s well-established populations in these areas.

However, some translocations can fail. In 1970 and 1971 a total of 93 animals from Amchitka Island were released near Port Orford and Cape Arago on the southern Oregon coast. Scientists now understand that, in addition to lack of monitoring and supplemental releases, a large number of animals immediately emigrated, leaving the area immediately after release thus reducing the population below a survival threshold. Despite some pupping success and seeming adaptation to the environment, by 1981 all animals were gone. Similarly, a translocation in the mid-1980s of animals from the California coast to San Nicolas Island in the Channel Islands nearly failed as the number of animals dropped sharply soon after release. It took several decades for the population to increase to become a viable and begin to expand, a pattern that scientists have come to see as a common one in the dynamics of translocation.

Traveling the Path

The Elakha Alliance has set out on an ambitious path. Like the return of the California condor to the remote cliffs of Utah and Arizona or the return of Grey wolves to Yellowstone National Park, returning sea otters to Oregon will take time, cooperation among many partners, public support, a sound scientific basis, and sustained funding.

To navigate this path, the Alliance in 2019 developed a strategic plan that describes its mission: To restore a healthy population of sea otters to the Oregon coast and to thereby make Oregon’s marine and coastal ecosystem more robust and resilient.

The plan also lays out two straightforward strategies: one is to complete scientific assessment and public policy analysis necessary to determine the feasibility and impacts of restoring and protecting a healthy sea otter population in Oregon. In other words, use science to guide the discussion and decisions. The second is to build regional consensus that a restored, healthy Oregon sea otter population is an important goal worth pursuing. In other words, make sure that the public supports this idea.

If those two goals are met, then a third strategy will come into play: Complete a restoration of a viable, sustaining population of sea otters to a few suitable places on the Oregon coast.;

Any decision about an actual restoration project is several years away and will be made by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, which has legal authority over sea otters. After that, it will take time to plan and raise funding for an expedition to bring animals to the Oregon coast and then do the necessary monitoring. Hence, the timeline for returning sea otters may approach a decade even if all goes well.

In the meantime, the Alliance is doing its homework to understand the details of potential restoration. It has contracted for a science-based Feasibility Study and related Economic Impact Assessment. Both studies aim to have public review drafts by Fall, 2021 and be completed by early 2022.

The Feasibility Study is examining a wide range of factors that will inform whether or not restoring sea otters to Oregon is, in fact, feasible and, if so, what sidebars and considerations will be necessary. This study, funded by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, is being written by a team of well-known scientists, including James Estes who first described the ecological importance of sea otters, and others with expertise in sea otters, previous translocations, veterinary medicine, and the marine environment of the Oregon coast.

The Economic Impact Assessment, based on potential “what if” scenarios in the Feasibility Study, is aimed at estimating the potential economic effects, both positive and negative, of bringing sea otters back to Oregon. That assessment is being conducted by a team of professionals with deep experience in the economics of Oregon’s coastal communities and fisheries. Funding for this assessment is coming from multiple sources such as the Oregon Conservation and Recreation Fund, the Oregon Coast Visitors Association, and a very generous private gift.

The Alliance has also mounted a robust program of public outreach and engagement with major funding support from the Meyer Memorial Trust as well as smaller funders and individuals. Even with the restrictions on in-person gatherings imposed over the past year, on-line technologies such as “Zoom” have proven a boon by enabling people from far and wide to participate in webinars and other programs. More than 400 people watched and learned from a three-day sea otter science symposium held in late 2020. Many hundreds have joined webinars sponsored by the Alliance or by other groups such as Shoreline Education for Awareness in Bandon, the Southcoast Watersheds Council in Gold Beach and the Mid-coast Watersheds Council in Newport. Social media platforms such as Facebook and Instagram have helped to expand awareness of and engagement in the effort to restore sea otters to Oregon. The Alliance has mounted a website rich in information and learning resources related to sea otters and kelp ecosystems.

But there is a long way to go. Finding the funds necessary to support this work over a decade is certainly a challenge. Even though sea otters appear to have a very high public approval rating, not everyone is thrilled with the idea of their return. Crab fishermen are concerned that sea otters, which eat crab, will take a bite out of their catch or that restrictions to protect sea otters will affect their operations at sea even as they must also avoid entangling Grey whales in their gear. The Alliance is committed to hearing and addressing such concerns.

Looking Ahead

A glimpse of the future, though, may be seen by an innovative population model being used by the Feasibility Study and Economic Assessment teams to project how many sea otters there might be and where they might be in the years following release. The model, based on population research in Alaska, Washington, and California, shows that the number of animals released will always decline sharply as many immediately leave the area. A sufficient number of enough animals must therefore be captured and released to allow for that drop in numbers as well as death from other causes while ensuring that enough animals, male and female, survive as the core of a self-sustaining population. Research shows that thirty years appears to be a realistic time frame by which to judge whether a population is self-sustaining and on track to grow.

To enable the team of economists to assess potential impacts of sea otters on coastal fisheries and local economies, the study teams created a set of 30-year “what if” scenarios of 100, 200, or 300 animals at each of four different locations. For example, to achieve a self-sustaining population of 100 animals in a particular area after 30 years, how many animals would be required to be released and at what locations? The answer is between 80 and 120 animals depending on the location and whether smaller additional releases are used to supplement the initial number to help offset emigration. The model also shows that, in general, the population will remain in the region close to the initial release site and will not have spread everywhere along the Oregon coast.

This modeling has laid bare some of the logistical and financial realities of capturing, transporting, releasing, and monitoring even 100 or even 200 animals, enough to ensure a self-sustaining population after 30 years. Those who visualize many hundreds of sea otters up and down the Oregon coast soon after release will probably be surprised, if not disappointed, that this will not be the case. As on the Washington and California coasts, sea otters in Oregon will likely be found within a fairly discrete core region for decades as the population slowly increases in number and expands its range. But through such modeling and assessment, we can now begin to see the outlines of what it will take to truly restore this iconic species to the Oregon coast.

This glimpse of the future, along with knowledge of the potential benefits, confirm that the journey foreseen by David Hatch and continued by the Elakha Alliance is possible – in fact, is necessary. It will take time after animals are returned to Oregon, many decades, to repair the torn ecological fabric of the Oregon coast and to restore the cultural bonds between sea otters and Indian people. While many of those now working for this future will not live to see the return of sea otters at such places as Otter Point or Otter Rock, their children and grandchildren fifty years from now certainly will.

Robert Bailey has spent nearly 40 years in coastal and ocean planning and management for the State of Oregon, most recently as the manager of the State of Oregon Coastal Management Program. He is the current president of the board of the Elakha Alliance. (email Robert)

Peter Hatch is a member of the Confederated Tribes of Siletz Indians, and works in the tribe’s Cultural Resources office. He’s been fishing, clamming and crabbing in Lincoln County his entire life, and wants to ensure that his descendants can always do the same. He is the current secretary of the Elakha Alliance. (email Peter)

Watch Elakha Alliance’s webinar, “The Return of Oregon’s Sea Otters: Considering the Cultural Dimensions of Restoration.”

Comments, thoughts or questions? Email us now!